Electric school buses are rolling out across the country due to historic federal and state investments made to support the replacement of existing diesel school buses with low and zero-emission alternatives. The North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center (NCCETC), through its Clean Transportation program, stands at the forefront, assisting fleets eager to leverage grant or rebate funds for cleaner, more sustainable transportation options and infrastructure.

Electric school buses are rolling out across the country due to historic federal and state investments made to support the replacement of existing diesel school buses with low and zero-emission alternatives. The North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center (NCCETC), through its Clean Transportation program, stands at the forefront, assisting fleets eager to leverage grant or rebate funds for cleaner, more sustainable transportation options and infrastructure.

In a recent webinar titled “Seasoned Fleet Managers’ Straight Talk on Electric School Buses,” experienced fleet managers from the Southeast region, including Donnie Owle of Cherokee Boys Club Inc., Paul D’Andrade of Fairfax County Virginia Public Schools, Hope Watts of Lynchburg Virginia Public Schools, and Wendy Anderson of Randolph County Public Schools, shared insights into their experiences with acquiring and deploying electric school buses. The full webinar, hosted by NCCETC’s John Bonitz and Rick Sapienza, is available to stream for free on GoToWebinar.

Donnie Owle, Service Manager and Vice President of the Cherokee Boys Club, discussed the successful integration of electric school buses into their fleet. With support from NCCETC, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) secured funds through the Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA) program, making them the first tribe east of the Mississippi to receive such grant funding.

Donnie Owle, Service Manager and Vice President of the Cherokee Boys Club, discussed the successful integration of electric school buses into their fleet. With support from NCCETC, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) secured funds through the Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA) program, making them the first tribe east of the Mississippi to receive such grant funding.

Owle initially had reservations when considering the possibility of adding electric school buses to his fleet. “First two things I thought about were power and how they were going to do here in the mountains – and how long is the battery going to last?” said Owle.

Being able to experience the power of an ESB on a ride-along persuaded Owle to change his mind. Owle and other CBC staff members traveled to High Point, NC where the school bus manufacturer Thomas Built Buses, Inc. is headquartered. “They really impressed me on how long the battery will last,” Owle recalled.

NCCETC staff played a central role in this initiative, collaborating closely with the CBC to assist in the grant-writing process and conduct emissions quantifications. These services were helpful in assessing the potential reduction in air pollution from the retirement of older, polluting buses and the subsequent deployment of new, zero-emission electric school buses.

The success of this collaboration underscores the commitment of both the EBCI and NCCETC in spearheading innovative solutions for cleaner, more sustainable transportation in the region. The EBCI and CBC are the first school bus fleet in North Carolina, and among the first in the Southeast, to commit to a pathway towards 100% electrification.

As part of NCCETC’s Clean Transportation program, Bonitz has been providing ongoing technical support to EBCI and the CBC transportation division, which operates the bus system for Cherokee Central Schools on the Qualla Boundary. He guided CBC staff through the meticulous documentation process of disabling and scrapping old diesel buses, ensuring compliance with the EPA’s DERA program.

“We just completed the process of permanently retiring EBCI’s old diesel school buses as part of the EPA’s funding requirements,” said Bonitz. “The EPA has a detailed process for scrapping the old buses which had to be completed within 90 days of receiving the new electric school buses to ensure the funds are being used to replace and remove polluting vehicles from the road, for good.” Pictured is Katie Tiger, an Environmental Specialist with the EBCI, posing as the engine of a retired diesel bus is destroyed.

“We just completed the process of permanently retiring EBCI’s old diesel school buses as part of the EPA’s funding requirements,” said Bonitz. “The EPA has a detailed process for scrapping the old buses which had to be completed within 90 days of receiving the new electric school buses to ensure the funds are being used to replace and remove polluting vehicles from the road, for good.” Pictured is Katie Tiger, an Environmental Specialist with the EBCI, posing as the engine of a retired diesel bus is destroyed.

Diesel school buses emit harmful pollutants into the air, including nitrogen oxides and particulate matter. Diesel exhaust from these buses can cause poor air quality in addition to a myriad of health problems such as asthma and heart disease. Children are especially vulnerable to air pollution both inside and near diesel school buses due to their underdeveloped lungs and faster breathing rate when compared to adults.

Bus drivers, school staff, students and community members can all benefit from the implementation of low- and zero-emission vehicles. The use of electric school buses results in cleaner air on the bus, along the bus route and in loading areas, as well as in the communities in which they operate.

Paul D’Andrade, Assistant Director of Transportation for Fairfax County Public Schools, emphasized the operational benefits of electric school buses. “We’re seeing significant savings when it comes down to fueling, between charging versus diesel and also for maintenance,” he reported.

D’Andrade elaborated on the cost savings from electric school buses: With reduced fuel expenses, eliminated fluid changes, and fewer mechanical parts in need of maintenance, electric school buses have proven lower operational costs than their diesel counterparts. The positive impact extends to reduced brake wear, thanks to regenerative braking technology.

Funding Opportunity Available Now: 2023 Clean School Bus Program Rebates

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) of 2021 provides $5 billion over 5 years (2022-2026) to support the replacement of existing school buses with clean or zero-emission school buses under Title XI: Clean School Buses and Ferries. Under this law, the EPA was authorized to administer rebates, grants, and contracts, aiming to replace a significant portion of the country’s fleet of approximately 500,00 school buses with environmentally friendly and zero-emission models to mitigate the adverse emissions from older, more polluting buses.

Under the Clean School Bus (CSB) Program, fifty percent of the allocated funds are specifically earmarked for the adoption of zero-emission school buses, while the remaining fifty percent is designated for the acquisition of clean school buses. A zero-emission school bus is defined as a vehicle that generates no exhaust emissions of air pollutants or greenhouse gasses while a clean school bus is characterized as a bus that diminishes emissions and operates either wholly or partially on alternative fuel.

The EPA is currently accepting applications for the 2023 CSB Rebate Program through January 31, 2024. This is the third round of funding offered through the CSB program and $500 million has been made available to public school districts, tribal applicants, and third parties such as nonprofit school transportation associations and eligible contractors.

The EPA is currently accepting applications for the 2023 CSB Rebate Program through January 31, 2024. This is the third round of funding offered through the CSB program and $500 million has been made available to public school districts, tribal applicants, and third parties such as nonprofit school transportation associations and eligible contractors.

As stipulated in law, prioritization is given to certain CSB applicants, including high-need and rural school districts, school districts funded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and school districts that support children who reside on Indian land. Applicants requesting funding that meet the prioritization criteria are eligible for increased funding per bus and benefit from preferential consideration in the selection process.

The 2023 CSB Rebate Program will provide up to $345,000 per ESB to cover the purchase of the bus and related electric vehicle charging infrastructure. More information regarding the selection process and prioritization can be found on the EPA’s website here.

Another important fund source is NC’s Department of Public Instruction (DPI), which covers a minimum of $100,000 per electric bus that replaces an old diesel bus already scheduled for replacement. In some cases, depending on bus specifications, the DPI contribution may be as high as $125,000.

Duke Energy is also helping contribute to the costs of electric bus charging infrastructure. Their EV Charger Prep Credit is worth many thousands of dollars, based on specifics of the charger and usage, as determined by an online calculator.

“For prioritized applicants, it looks very good: Between EPA’s $345k, DPI’s $100k, charger prep credit from Duke Energy, and the IRS tax credit elective payments on bus and charger, prioritized applicants can be confident their costs will be covered,” said Bonitz.

The Inflation Reduction Act also offers tax credits which may be applicable to help cover the cost of bus and infrastructure purchases, even for tax-exempt entities like local governments and school districts. The Commercial Clean Vehicle Credit provides up to $40,000 for qualified clean vehicles and the Alternative Fuel Vehicle Refueling Property Credit provides up to $100,000 for qualified charging and refueling infrastructure.

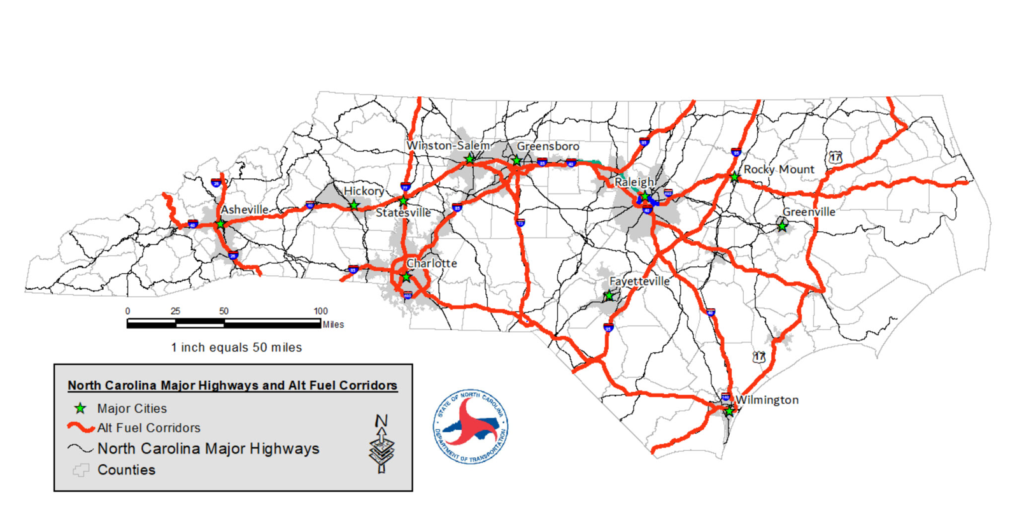

In North Carolina, the Clean Fuel Advanced Technology (CFAT) program provides annual funding for clean transportation technologies in eligible counties across the state. CFAT funding, administered by NCCETC, helps private and public fleets purchase clean transportation technologies to improve North Carolina’s air quality.

In North Carolina, newly available funding sources are more than enough to cover all costs of ESB projects for certain applicants. Because EPA prioritizes a list of high-need local education agencies, rural areas, disadvantaged communities, etc., such as North Carolina’s Tier 1 counties and Historically Under-Resourced Counties, they offer a more generous rebate for projects by these prioritized applicants. In many cases, available incentive funds will cover 100% of the project costs, especially for underfunded, disadvantaged, and rural school districts. As John Bonitz describes, “For prioritized applicants, it looks very good: Between EPA’s $345k, DPI’s $100k, charger prep credit from Duke Energy, and the IRS tax credit elective payments on bus and charger, prioritized applicants can be confident their costs will be covered.”

In North Carolina, newly available funding sources are more than enough to cover all costs of ESB projects for certain applicants. Because EPA prioritizes a list of high-need local education agencies, rural areas, disadvantaged communities, etc., such as North Carolina’s Tier 1 counties and Historically Under-Resourced Counties, they offer a more generous rebate for projects by these prioritized applicants. In many cases, available incentive funds will cover 100% of the project costs, especially for underfunded, disadvantaged, and rural school districts. As John Bonitz describes, “For prioritized applicants, it looks very good: Between EPA’s $345k, DPI’s $100k, charger prep credit from Duke Energy, and the IRS tax credit elective payments on bus and charger, prioritized applicants can be confident their costs will be covered.”

With such an abundance of funding sources available for purchasing electric school buses, these funds can be “braided” together to cover 100% of the project costs, especially for underfunded, disadvantaged and rural school districts. NCCETC has published a fact sheet with information about these funding sources and includes a spreadsheet that can be downloaded to create a draft budget to estimate project costs.

The transition to electrify school buses in the United States represents a commitment to the well-being of our communities and the environment. The continuous collaboration between NCCETC and pioneering fleets exemplifies the collective effort required to build a sustainable future, one electric school bus at a time. As we deploy these cleaner and more efficient modes of transportation, we create a future where our children can breathe easier, learn safer, and travel sustainably.

To help customers navigate the variety of direct financial incentives available for EVs and EV fueling infrastructure, NCCETC previously published the guidance document

To help customers navigate the variety of direct financial incentives available for EVs and EV fueling infrastructure, NCCETC previously published the guidance document